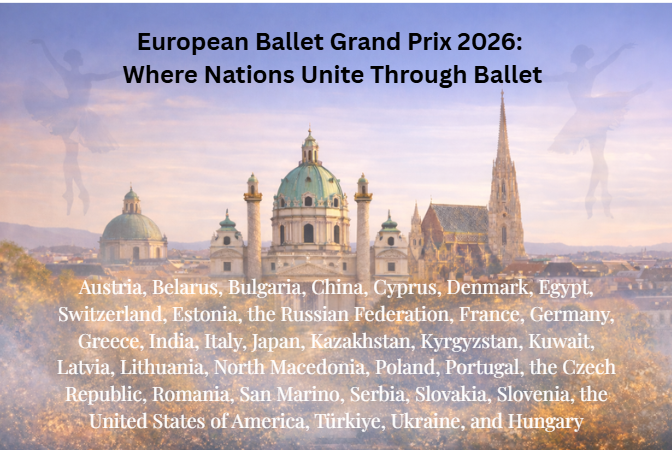

Bringing the World of Ballet Together in Vienna – European Ballet Grand Prix 2026 with Dancers from 35 Countries

by Simona Noja-Nebyla, Founder & Organizer of European Ballet Grand Prix

Vienna has always been a city where tradition meets excellence, where music and dance are not only art forms, but a way of life. It is therefore with great pride and deep responsibility that I welcome dancers, teachers, choreographers, and ballet lovers from around the world to the 9th edition of the International Ballet Competition “European Ballet Grand Prix”, taking place in Vienna from February 4–6, 2026.

What began years ago as a vision—to create a truly international platform dedicated to young ballet talent—has grown into a global meeting point for artistic exchange, professional development, and cultural dialogue. Today, the European Ballet Grand Prix stands as a respected international competition that values not only technical excellence, but also individuality, artistry, and personal growth.

A Truly Global Community

The 2026 edition of EBGP will welcome participants from 35 countries across Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Americas. This remarkable diversity is one of the greatest strengths of our competition. Each dancer brings with them not only their training and ambition, but also the cultural richness of their home country—transforming the EBGP stage into a celebration of global ballet culture.

Seeing young artists share the stage, support one another, and learn from an international jury reaffirms why this project matters. Ballet is a universal language, and EBGP exists to give that language a space to be heard, respected, and nurtured.

More Than a Competition

European Ballet Grand Prix is not only about awards. It is about mentorship, opportunity, and inspiration. Through professional feedback, encounters with renowned jury members, and exposure to an international audience, dancers gain experiences that shape both their artistic and personal journeys.

Vienna offers the perfect setting for this mission—a city with a deep cultural heritage and an open, international spirit. Hosting EBGP here is both an honor and a promise: to uphold the highest artistic standards while encouraging the next generation of ballet professionals.

Looking Ahead to February 2026

As we prepare for this upcoming edition, I would like to thank all participants, teachers, partners, and supporters who continue to believe in the values of European Ballet Grand Prix. Your dedication is what allows this event to grow year after year.

I warmly invite audiences to join us in Vienna and experience three unforgettable days of passion, discipline, and artistry at the highest level.

I look forward to welcoming you personally to Vienna.

With appreciation,

Simona Noja-Nebyla

Founder & Organizer

European Ballet Grand Prix – Vienna

Striking the Right Note: Renato Zanella as Ballet Director at Teatro di San Carlo

There are moments in music and art—and in history—when everything aligns on a single, resonant note. In Naples today, that note is a Si bemol: warm, expansive, and unmistakably European. With the appointment of Renato Zanella as the new Ballet Director of Teatro di San Carlo, the world’s oldest continuously active opera house strikes a chord that reverberates far beyond the Bay of Naples.

A European Journey, Danced in Many Languages

Zanella arrives in Naples carrying a rare passport—one stamped by the great ballet capitals of Europe. His directorships at the Wiener Staatsoper, Opera Națională București, Greek National Opera, and the Slovenian National Opera Ljubljana have forged a leadership style fluent in classical rigor and contemporary curiosity.

In Vienna, he refined tradition to a gleam; in Bucharest, he expanded repertory with bold intelligence; in Athens, he bridged antiquity and modernity; in Ljubljana, he shaped a cosmopolitan voice from a crossroads of cultures. Each post added a register to his artistic range—now ready to be played in Naples.

Naples as Magna Graecia, Yesterday and Today

To understand why this appointment feels inevitable, one must look beyond the stage and into the city itself. Naples is not merely Italian; it is Magna Graecia—a place where Greek thought, Roman order, and Mediterranean spirit have intertwined for over 2,500 years.

Here, ideas have always traveled. Philosophers, musicians, merchants, and artists crossed seas to meet, argue, and create. The Teatro di San Carlo—older than La Scala and the Paris Opéra—is the architectural embodiment of this legacy: a house built to welcome the world and send it back transformed.

A Contemporary Si bemol

In musical terms, Si bemol softens sharp edges; it opens harmony, invites collaboration, and deepens color. Zanella’s arrival signals just that. His vision is neither provincial nor rootless—it is Napoli-centric and world-facing, honoring the city’s history while aligning it with the best international practices in ballet today.

This is not about importing a foreign style, but about connecting excellence—the Neapolitan musical soul with European choreographic intelligence, classical heritage with contemporary movement. Exactly as Naples has done for centuries.

The World, Centered on a Stage

As curtains rise on this new chapter, the message is clear: Naples is once again a meeting point. From Vienna to Athens, from Bucharest to Ljubljana, artistic energies converge at the San Carlo—not by chance, but by historical gravity.

Hitting the Si bemol means choosing resonance over noise, depth over spectacle. With Renato Zanella at the helm, the Ballet of Teatro di San Carlo doesn’t just keep time—it sets the pitch for what a truly international, historically grounded, and forward-looking ballet institution can be.

With Renato Zanella as Ballet Director, Teatro di San Carlo strikes the right note—where Naples’ Magna Graecia heritage and a global ballet vision meet in lasting harmony.

Baletul New Generation al Academiei Naționale de Muzică «Gheorghe Dima» – dansul ca vocație, continuitate și recunoaștere

Foto credit Ada Gonzalez@TBS Ovidiu Matiu

Baletul New Generation al Academiei Naționale de Muzică «Gheorghe Dima» – dansul ca vocație, continuitate și recunoaștere

Prin alegerea denumirii New Generation, Academia Națională de Muzică „Gheorghe Dima” afirmă identitatea unui proiect artistic dedicat exclusiv dansului, conceput ca spațiu de afirmare a baletului și artei coregrafice în deplină consonanță cu valorile academice și artistice ale instituției. NEW Generation nu este doar un titlu sugestiv, ci expresia unei viziuni coerente asupra formării noilor generații de dansatori, în care tradiția, rigoarea și deschiderea spre excelență coexistă armonios.

Într-un cadru instituțional deja consolidat prin existența unor ansambluri cu identitate distinctă – Ansamblul Ars Nova, Corul Ave Musica, Orchestra „Antonin Ciolan”, Ansamblul de flaute Il Gardellino – compania de tineret NEW Generation completează acest tablou artistic printr-o direcție clară și asumată: dansul ca limbaj scenic autonom și ca domeniu academic matur.

Transformarea secției de dans în Coregrafie și Coreologie

Evoluția domeniului coregrafic în cadrul Academiei Naționale de Muzică „Gheorghe Dima” este indisolubil legată de activitatea Conf. dr. abil. Nicoleta Demian, care a fost inițiatoarea transformării secției de dans în Secția de Coregrafie și Coreologie. Acest demers a reprezentat un pas esențial în recunoașterea dansului ca disciplină artistică și teoretică de sine stătătoare, integrată deplin în structura academică a instituției.

Transformarea nu a fost una formală, ci profund conceptuală: de la o abordare predominant practică a dansului, la un cadru universitar complex, în care creația scenică, pedagogia, analiza mișcării și reflecția teoretică coexistă și se susțin reciproc.

Baletul – excelență artistică și loialitate față de tineri

Spectacolul Lacul lebedelor, prezentat la Sala Heritage a Academiei de Muzică, pe 14 decembrie 2025 în colaborare cu Orchestra New Hope, condusă de Octavian Lup, a marcat primul proiect al companiei de tineret NEW Generation și, totodată, o expresie elocventă a valorilor cultivate în timp în cadrul secției: calitatea artistică, rigoarea profesională și loialitatea față de tinerii studenți.

Distribuția a reunit, într-un echilibru atent construit, studenți ai Academiei și artiști consacrați ai scenei lirice bucureștene, generând un dialog autentic între generații. În Actul I, Valsul a fost susținut de Ariana Marcu, Alexandra Nuna, Alexandra Fîlfan, Teofana Varga, Tudor Crețan și Mihai Pop, într-o construcție de ansamblu coerentă, în care precizia mișcării și omogenitatea grupului au fost esențiale. Romanța/Balada prințului Siegfried, interpretată de Bogdan Cănilă, prim-balerin al Operei Naționale București, a adus o dimensiune lirică și introspectivă, conturând cu finețe profilul dramatic al personajului.

Actul II a pus în valoare disciplina și sincronizarea prin scena lebedelor – Andreea Aron, Bianca Busuioc, Smaranda Ciubotariu și Anca Toke – moment de referință pentru rigoarea baletului clasic. Adagio-ul și coda Lebedei Albe, interpretate de Ada Gonzalez și Bogdan Cănilă, prim-balerini ai Operei Naționale București, au constituit un reper de excelență artistică și un model de expresivitate și rafinament pentru tinerii dansatori.

În Actul III, dansurile de caracter au adus diversitate stilistică și dinamism scenic: dansul spaniol (Ariana Marcu), dansul napolitan (Alexandra Nuna, Alexandra Fîlfan, Teofana Varga) și dansul maghiar (Bianca Busuioc și Mihai Pop) au fost integrate coerent în dramaturgia spectacolului. Pas de deux-ul Lebedei Negre, interpretat de Eliza Selyem și Alexandru Moldovan, a evidențiat contrastul dramatic și forța expresivă a acestui moment central.

Actul IV a reunit ambele cupluri de soliști – duetul alb și duetul negru – într-o construcție finală echilibrată, care a consolidat unitatea dramaturgică a baletului și dialogul simbolic dintre lumină și întuneric, inocență și seducție.

Coregrafia, ansamblul și spiritul formativ al repetițiilor

Din punct de vedere coregrafic, spectacolul s-a remarcat prin claritatea organizării ansamblului și prin coerența limbajului clasic, susținute de un proces de repetiție riguros. Repetițiile au fost concepute ca un spațiu de formare artistică și umană, în care disciplina, dialogul și responsabilitatea scenică au avut un rol central, contribuind decisiv la maturizarea scenică a fiecărui interpret.

Un mesaj de recunoaștere

New Generation se afirmă astfel nu doar ca un spectacol-eveniment, ci ca un mesaj de recunoaștere a unei munci îndelungate, desfășurate cu perseverență, discreție și devotament. Prin inițierea transformării secției de dans în Coregrafie și Coreologie, prin susținerea constantă a tinerilor studenți și prin cultivarea legăturilor cu artiști consacrați, Conf. dr. abil. Nicoleta Demian a contribuit decisiv la maturizarea domeniului coregrafic în cadrul Academiei Naționale de Muzică „Gheorghe Dima”.

Acest spectacol confirmă că adevărata valoare artistică nu se măsoară doar prin performanța scenică, ci și prin capacitatea de a construi în timp, de a forma generații și de a crea un spațiu de loialitate, respect și continuitate artistică.

Earth Works by Sergiu Matis, at the Vienna Odeon Theater, on July 11, 2025, as part of ImPulsTanz Festival 2025

by Simona Noja-Nebyla

Earth Works is a dance piece by Sergiu Matis, a Romanian choreographer born in Cluj-Napoca and educated in Romania and Germany. Premiered in December 2024 in Berlin, it draws on reflections by authors from different parts of the world, recounting their personal experiences with the threatened environment.

Through words, sentences, and images, the text carries the five performers: Lisa Densem, Moo Kim, Sergiu Matis, Nicola Micallef, and Manon Parent, who, in turn, embody the movements generated by the written and spoken word in space. In this live exchange of knowledge, we, the audience, encounter ancestral essences of cultures (often unfamiliar to most Europeans) and their messages.

Metaphors like “Water is the first story of place” or “A river is the song of running water” echo within us the ancient Greek memory of Thales of Miletus, who believed that everything began with water. There is an immediate connection between us and the Wiradjuri belief (Australia) as “people of the rivers.” We recognize that rivers belong to all of us, that they, like us, want to keep flowing, evolving. Jeanine Leane goes even further: “Rivers are us.” As long as water can flow, there is life—something that should never be stopped or broken. “If a deity is a force that can either create or destroy all life, then water is our highest power. What retribution will the future bring if we fail in our reverence for rivers?” [Leane, J. (2025). Galing-gu giiland. In Earth Works (Performance program, pp. 6–8). Vienna.]

Translated into movement, the dancers know no boundaries of embodiment; they are alive as long as they can move and bring ideas into manifestation. Through their bodies, the dancers let truth flow. If words may abstract meaning, the dancers carry the detailed significance of each thought, delivering it into virgin territories of sense—making it visible, perhaps newly understood, and why not, loved for the first time.

Photo@Boris Nebyla

Wiradjuri poetry is polyphonic; it holds ancestral voices, personal memory, communal trauma, language, resistance—all together, in a layered and powerful way. In a Western literary context, this idea is famously explored by Russian thinker Mikhail Bakhtin, who described the novels of Dostoevsky as “polyphonic”, allowing multiple moral, social, and philosophical voices to speak without the author imposing one “final truth.”

Is polyphony a renewal of the syncretic primordial arts?

Does bringing many voices together in poetry or art revive an older, foundational way of making art—one inherently blended, ritualistic, communal, before divisions like “high” and “low” art or “Western” and “Indigenous” systems?

In the context of Wiradjuri poetry (and many Indigenous poetics), polyphony is not a postmodern innovation; it’s a continuation of ancient practices. Oral traditions have always been multi-voiced: ancestor stories, songlines, past and present intertwined. Colonialism tried to flatten or silence this multiplicity, though poets like Jeanine Leane reclaim and re-weave those many voices—it’s both renewal and resistance.

But polyphony isn’t always syncretic in the sense of blending traditions into one. Sometimes, it’s about holding differences without erasure. For example, English and Wiradjuri languages can sit together in a poem without merging — they rub, resist, echo, but don’t collapse into a single hybrid.

The five dancers do something similar. Their polyphony of movement, shaped by different backgrounds, acts as a renewal of long-forgotten, deeply anchored emotions — vivid now as they were back in time. Modern systems may have suppressed this, but movement often goes beyond words, carrying secrets that only human bodies can hold.

More than that, in Earth Works, the return to origins carries less the weight of nostalgia and more the hidden, mysterious, transformative power of revealing the truth.

“In order to understand, sometimes we have to go back to the beginning. [...] Our ancestors measured distances through an understanding of currents [the Pacific Ocean] by feeling the breeze and following a map of the stars with a map that existed in the mind, and was transmitted down through generations via storytelling and connection to the environment.” [Aoake, H. P. (2025). Whatungarongaro te tangata, toitu te whenua — people fade away, but the land remains. In Earth Works (Performance program, pp. 10–21). Vienna.]

The “huge body of water with dotted islands in between big continents” can be seen as a giant wheke (octopus) that interconnects pieces of land across the ocean, suggests Hana Pera Aoake, a New Zealand author and researcher. She suggests that if we understand our whakapapa (foundational explanation not only for why life came to be, but also how it should be lived), we are grounded to the earth and know where we belong.

An explanation might be needed here: the Australian Wiradjuri are distinct from the Māori.

Both Māori (Aotearoa/New Zealand) and Wiradjuri (Australia) are Indigenous peoples with deep ancestral ties to their lands, not just as territory, but as living kin (whenua in Māori, Ngurambang in Wiradjuri). Both hold worldviews where human, non-human, spiritual, and natural worlds are interconnected. Ancestors, animals, rivers, mountains, and plants are seen as living beings or relatives. While Māori are Polynesian (part of the larger Austronesian family), having sailed to Aotearoa around the 13th century from eastern Polynesia, the Wiradjuri are Aboriginal Australians, part of one of the oldest continuous cultures on Earth (60,000+ years), with completely different ancestral origins and migration history.

As Hana Pera Aoake suggests, the performers of Earth Works seem to know where they belong. Sergiu Matis lets his roots of Romanian culture — shaped by layered influences (Roman, Slavic, Balkan, and more) — braided over time into a singular, living tradition — meet other cultures with ease, respect, and curiosity. The Māori worldview becomes close and familiar, because “we don’t own land, we belong to it” (Hana Pera Aoake). It looks like a fairy tale. Sometimes, it can become a horror. But dancers give us hope. They remind us how we can rewrite stories about places that are sacred, as in Māori belief, “of the beauty of Te Wai u o Tūwharetoa that has not yet been destroyed.” (Hana Pera Aoake).

This might not be easy. As the Nigerian Rahima Gambo asks herself:

“Is natural catastrophe an exercise in abstract expressionism, a Pollock canvas waiting to happen? In natural catastrophe, there may be no answers, but there is music, improvised and lilting, moving from note to note, until it reaches a chaotic frenzy.” [Gambo, R., with Tatsuniya Artist Collective. (2025). Termite splatter. In Earth Works (Performance program, pp. 24–25). Vienna.]

Yes, there might be hope where we can see music and hear dance. Yet, we must pay attention to “a special rock somewhere”—because if mined, “Jamaica will sink”. “A sinking island within this mytho-poetic landscape is not only water rising but the land itself folding in on itself.” [Morrison, H. (2025). “A special rock somewhere”. In Earth Works (Performance program, pp. 28–29). Vienna.]

There is danger everywhere, and “the blood wants to fly.” We are “alone but not really.” The fire hidden by the mangroves reminds us, in a Heraclitean way, that all things transform constantly. It suggests that the spirit, memory, or cultural presence of the Javan tiger continues, even if the animal no longer exists physically. It evokes resilience, survival, or wildness that persists against all odds. “Lineage is not a downward line.” Even colonialism could not destroy it. Because lineage is not just ancestry flowing from past to present in a straight, vertical line—parent → child → grandchild. Lineage is relational, circular, and web-like. In many Indigenous and relational worldviews (including Wiradjuri and Māori), lineage is not linear but networked—it includes relationships across generations, non-human kin (animals, plants, rivers), ancestors and future descendants, land, memory, and spirit. Lineage is responsibility, not just inheritance. It’s not only what you get from those before you, but what you carry, care for, and pass in multiple directions. It radiates in many directions: backward to ancestors, sideways across the community, forward to those yet to come, and outward to land and more-than-human relations. [Jay, P. (2025). My blood wants to fly. In Earth Works (Performance program, pp. 32–34). Vienna.]

In this sense, the destinies of human beings are deeply entangled with the elements of nature and plants. “Suddenly life is a flower, a small flower by a lakeshore” [Valkeapää, L., & Valkeapää, O. A. (2025). Life is... In Earth Works (Performance program, pp. 36–37 Vienna.)] As Leena and Oula A. Valkeapää, following the Sámi tradition of the people of Lapland (Finland), live with reindeer and believe, these animals are ancestral beings, part of our cosmic and shamanic journeys. They are central life-givers—providing food, clothing, tools, mobility, and spiritual connection. Beyond that, the reindeer embodies cycles of life, migration, survival, and reciprocity with nature. Across cultures, mythological readings often see reindeer as mediators between worlds (earth-sky, human-spirit, living-dead), carriers of light and movement through darkness (especially in the polar night).

Is the reindeer not similar to a dancer—a cosmic traveler bringing a lifeline across space and time, performing a movement that occurs here and now, between river and ocean?

Photo@Boris Nebyla

Even if Sergiu Matis tends to believe that “Nothing remains” (2024), his unpublished poem, Earth Works is a poetic dance plea about ephemerality and disappearance, environmental grief and embodied memory. And even if it echoes a meditation on endings, one feels it deeply also as a provocation: what might endure beyond ruin?

Photo@Boris Nebyla

A river as the song of running water?

A special rock somewhere?

A small flower by a lakeshore near reindeer?

Or maybe it is only our meaningful, daring effort to understand the whakapapa through dance?

Photo@Boris Nebyla

Credits

Concept & Choreography

Sergiu Matis

Performance

Lisa Densem, Moo Kim, Sergiu Matis, Nicola Micallef, Manon Parent

Text Contributors

Hana Pera Aoake, Rahima Gambo, Priya Jay, Jeanine Leane, Harun Morrison, Leena Valkeapää, Oula A. Valkeapää

Dramaturgy

Mila Pavićević

Music

Antye Greie-Ripatti (AGF)

Set & Lighting Design

Ladislav Zajac

Costume Design

Lisa Densem, Philip Ingman, Moo Kim, Sergiu Matis, Nicola Micallef, Manon Parent

Choreographic Assistance

Laurie Young

Technical Direction & Sound

Andrea Parolin, Ivan Bartsch

Voice Coaching

Jule Flierl

Editorial Direction

Harun Morrison

German Translation

Calvin Lanz

Production

Anna Chwialkowska, Philip Ingman

Distribution & Touring

Philip Ingman

Production Information

A production by Sergiu Matis

Funded by Hauptstadtkulturfonds, Berlin (DE)

Co-produced by Teatro Nacional Dona Maria II Lisbon (PT) as part of apap – FEMINIST FUTURES (funded by the Creative Europe Programme of the European Union), PACT Zollverein Essen (DE), Radialsystem Berlin (DE), Tanzfabrik Berlin (DE)

Supported by Kunstencentrum BUDA Kortrijk (BE) as part of apap

O escală în smerenie: despre timp, aroganță și ce înveți când nu controlezi nimic.

Am ajuns în Brazilia pentru a mă confrunta cu propriile mele concepte despre timp și aroganță.

Dante avea un loc precis unde îi trimitea pe aroganți și era foarte riguros în clasificarea păcatelor. În viziunea sa din Divina Comedie, aroganța (trufia) este considerată o formă de mândrie exagerată — și este clasată drept unul dintre cele mai grave păcate capitale.

Ei nu sunt pedepsiți în Infern, ci apar în Purgatoriu. În Infern ajung doar cei care nu s-au căit niciodată. În schimb, în Purgatoriu ajung sufletele care au păcătuit, dar s-au căit înainte de moarte. Arogantul poate să se pocăiască. Dacă mândria nu duce la rău voit împotriva altora, ci este mai degrabă un defect personal, nu se încadrează în păcatele „finale” și „împietrite” ale Infernului.

Ei bine, arogantilor le revine Tărâmul Purgatoriului – Terenul celor mândri (trufași), mai exact Primul cerc al Muntelui Purgatoriului. Ca pedeapsă, ei poartă pietre uriașe pe spate, care îi obligă să meargă cocoșați și cu privirea în jos. Mândria i-a făcut să se înalțe; acum sunt forțați să se plece spre pământ.

Ca europeni, născuți și educați într-un spațiu îmbibat de cultură, tentația de a deveni trufași și de a practica aroganța celor care se cred superiori doar datorită locului din care vin este mereu activă. Cu atât mai mult când cineva trăiește într-o țară considerată, după standardele de viață, în topul mondial.

Ajungând în Brazilia, după 24 de ore de zbor și tranziții între avioane și aeroporturi, conceptele existențiale își pierd forma, fiind dezgolite de orice conținut. Percepția timpului, pentru un european funcțional, capătă aici alte conotații: dintr-o entitate abstractă, dar coerent clasificabilă, devine un fluid incontrolabil și indefinibil.

Am înțeles pentru prima dată, la propriu, ce înseamnă „timpul curge”. Minutele devin ore, orele devin inexorabil reflecție. Pe nimeni nu pare să deranjeze această curgere, cu excepția altor europeni aflați în aceeași stare de perplexitate ca mine.

Dacă ai pierdut avionul de legătură în São Paulo – al treilea în decurs de 24 de ore – a cărui poartă s-a închis inexplicabil înainte de ora anunțată, începe o odisee pe care nu o poți parcurge urmând logica europeană. Însă poți supraviețui doar dacă îți interoghezi propriul concept despre timp și aroganță.

Logic, îmi pun întrebarea: Ce trebuie să fac acum? Deși vorbesc cinci limbi, nu reușesc să mă fac înțeleasă de nimeni. Ciudat cum, din 230 de milioane de brazilieni, nimeni nu pare să vorbească vreo altă limbă!

Renunț să mai aștept ca alții să mă înțeleagă și încerc eu să înțeleg. Îi rog să vorbească portugheza lent – portugheza braziliană. Reușesc să identific câteva cuvinte care capătă sens.

Alerg spre diverse ghișee, într-un aeroport aflat la ora 5 dimineața, în semiîntunericul care face ton în ton cu întunericul de afară. Sute și sute de persoane vorbind portugheza braziliană (português brasileiro), cu intonarea ei melodioasă și lascivă, fluidizează nu doar timpul, ci și spațiul. Aeroportul devine un oraș pe care trebuie să-l parcurgi contra cronometru — după crezul european. Dar timpul, aici, se măsoară doar pe terenul de fotbal, nicidecum altundeva. E ca și cum ai alerga într-un spațiu vidat.

Este de-a dreptul sur-realist. Chiar se poate întâmpla așa ceva? Mai există, în secolul XXI, astfel de situații? Kafka rămâne actual: orice este oricând, în orice fel posibil.

La cele 25 de ghișee, nimeni nu lucrează. Două reprezentante ale liniei aeriene stau docile. Se așteaptă. Întreb. Nimeni nu știe exact. Toți sunt calmi. Doar un european plânge. Nu înțelege cum poți aștepta la ghișee unde, deși personalul este prezent, nimeni nu face nimic.

Și mă gândesc cum mă enervam în Austria că trenul avea întârziere de 10 minute și visam la Japonia, unde suma întârzierilor într-un an era mai mică de un minut și câteva secunde...

În São Paulo nu există întârziere, pentru că nu există timp.

Există doar o curgere a cuvintelor, spre o melodie a existenței, care te trimite la reflecție.

În timpul așteptării, încep să mă întreb:

Cum ar fi dacă aș practica mai mult smerenia? Față de oameni. Față de țări. Față de timp.

Oare nu ar fi mai „productivă” în fața dificultăților? Ale vieții. Ale oricărui aeroport.

Oare nu sunt spațiul, timpul și mișcarea doar entități pe care le modelăm noi?

Și cum ar fi dacă le-aș identifica, analiza, sintetiza, integra și trăi – nu doar logic, ci în credința smereniei?

Nu m-ar apropia mai mult de propriul conținut?

Despre relația dintre Istorie, Teorie, Estetică și Stil în Dans

Istoria, teoria, estetica și stilul sunt concepte profund interconectate care ne ajută să înțelegem nu doar cum dansăm, ci și de ce dansăm așa cum o facem.

🔹 Istorie

Istoria oferă contextul dansului. Ea urmărește evoluția mișcării, pedagogiei, spectacolului și scopului, de-a lungul diverselor culturi și epoci. Prin istorie înțelegem originile baletului — apariția sa în curțile regale, transformarea în perioada romantică și codificarea sa în tradițiile academice de astăzi. Fără conștientizarea istoriei, dansul devine deconectat de la moștenirea sa culturală și artistică.

🔹 Teorie

Teoria oferă cadrul prin care analizăm și interpretăm dansul. Ea abordează întrebări precum:

Ce definește dansul?

Care este relația dintre formă și semnificație?

Cum interacționează mișcarea, muzica și spațiul?

Teoria dansului face legătura între practică și înțelegere. Ea ajută dansatorii, profesorii și cercetătorii să articuleze logica și limbajul mișcării — transformând instinctul în cunoaștere.

🔹 Estetică

Estetica se ocupă de filosofia frumuseții și expresiei în dans. Se întreabă:

Ce face o mișcare să fie considerată frumoasă?

Cum percepem armonia, grația sau intensitatea?

De ce anumite gesturi sau forme ne emoționează?

În balet, estetica este influențată de idealuri istorice (ex: simetrie, verticalitate, épaulement), dar evoluează odată cu timpul și cultura. Valorile estetice ne influențează modul de pregătire, vizionare și interpretare a dansului.

🔹 Stil

Stilul este expresia vizibilă a tuturor celor de mai sus. El reflectă modul în care un dansator interpretează o mișcare în cadrul unui context istoric, estetic și teoretic. Stilul reflectă epoca, locul, școala și filosofia dansului. Nu este doar ce se dansează, ci și cum este întrupat acel dans.

🔗 Cum se leagă între ele

Istoria fundamentează teoria – cunoașterea trecutului ajută la analiză și predare cu profunzime.

Teoria clarifică estetica – înțelegerea structurii evidențiază frumusețea și intenția.

Estetica modelează stilul – valorile despre frumusețe ne influențează alegerile stilistice.

Stilul reflectă istoria – fiecare mișcare poartă amprenta momentului cultural.

Împreună, aceste concepte creează un continuum al cunoașterii care susține dezvoltarea intelectuală și artistică a dansatorilor și educatorilor.

🧩 Elemente comune între Istoria Dansului și Teoria Dansului

Context cultural și social

Ambele discipline evidențiază influențele culturale și sociale asupra dansului.Evoluția stilurilor și tehnicilor

Istoria urmărește transformările, iar teoria le explică în termeni de tehnică și structură.Ritual și simbolism

Dansul are un rol ritualic și simbolic, central în multe culturi.Funcții sociale ale dansului

Dansul poate fi ritual, divertisment, protest sau identitate națională.Relația cu alte arte

Dansul se intersectează cu muzica, teatrul, poezia sau artele vizuale.Mișcarea ca limbaj

Mișcarea este un limbaj universal — istoria o documentează, teoria o analizează.Corp și tehnică

Corpul este instrumentul de bază; teoria și istoria tratează dezvoltarea sa diferit.Estetică și valoare artistică

Teoria discută expresia, istoria urmărește evoluția idealurilor estetice.Influențe filosofice și teoretice

Existențialismul, fenomenologia sau psihanaliza au influențat dansul modern/contemporan.

🧩 Elemente comune între Teoria Dansului și Estetică

Frumusețe și expresivitate corporală

Ambele studiază cum mișcarea exprimă idei și emoții.Armonie și echilibru

Esențiale pentru o percepție estetică pozitivă.Relația cu muzica și ritmul

Teoria investighează adaptarea mișcării; estetica evaluează rezultatul artistic.Formă și stil

Teoria le clasifică, estetica le evaluează vizual și emoțional.Improvizație și spontaneitate

Apreciată pentru autenticitate și expresivitate.Emoție și simbolism

Dansul transmite semnificații, interpretate de public prin estetică.Originalitate și inovație

Valorile estetice și teoretice apreciază inovația stilistică.Relația dansator–public

Impactul asupra publicului este esențial pentru experiența estetică.Estetica mișcării și tehnică

O tehnică bună amplifică efectul estetic.Context cultural și tradiții

Cultura modelează percepția și aprecierea dansului.

🧩 Elemente comune între Estetică și Stil

Formă și structură vizuală

Stilul determină organizarea mișcărilor, estetica le evaluează.Expresivitate și emoție

Fiecare stil exprimă emoția diferit, ceea ce afectează percepția estetică.Originalitate și inovație

Stilul devine canalul prin care estetica se exprimă inovativ.Ritm și dinamism

Stilul definește ritmul; estetica analizează efectul său vizual și emoțional.Costume și prezentare vizuală

Stilul influențează alegerea costumelor; estetica judecă impactul lor.Influență culturală

Estetica și stilul sunt ancorate în valori culturale și istorice.Simbolism și semnificație

Stilul folosește vocabular specific, estetica decodifică semnificațiile.Impactul asupra publicului

Estetica analizează reacția publicului; stilul modelează această reacție.

On the Relationship Between History, Theory, Aesthetics, and Style in Dance

History, theory, aesthetics, and style are deeply interconnected concepts that help us understand not only how we dance but why we dance the way we do.

🔹 History

History gives us the context of dance. It traces the evolution of movement, pedagogy, performance, and purpose across different cultures and eras. Through history, we understand the roots of ballet—its origins in the courts, its transformation through Romanticism, and its codification into today's academic traditions. Without historical awareness, dance becomes disconnected from its cultural and artistic lineage.

🔹 Theory

Theory provides the framework through which we analyze and interpret dance. It explores questions like:

What defines classical ballet?

What is the relationship between form and meaning?

How do movement, music, and space interact?

Dance theory bridges practice and understanding. It helps dancers, teachers, and researchers articulate the logic and language behind movement—turning instinct into knowledge.

🔹 Aesthetics

Aesthetics concerns the philosophy of beauty and expression in dance. It asks:

What makes a movement beautiful?

How do we perceive harmony, grace, or intensity?

Why do certain gestures or forms move us emotionally?

In ballet, aesthetics are shaped by historical ideals (e.g. symmetry, verticality, epaulement), but also evolve with time and culture. Aesthetic values influence how we train, watch, and interpret dance.

🔹 Style

Style is the visible expression of all the above. It is how a dancer performs within a specific historical, aesthetic, and theoretical frame.

For example:

The lyrical softness of Romantic ballet

The sharp clarity of the Vaganova technique

The grounded power of contemporary movement

Style reflects the time, place, school, and philosophy behind the dance. It is not only what is danced but how it is embodied.

🔗 How They Relate

History informs theory: Knowing what came before helps us analyze and teach with depth.

Theory refines aesthetics: Understanding structure clarifies beauty and intention.

Aesthetics shape style: Our values about beauty guide our stylistic choices.

Style reflects history: Every movement carries the trace of a cultural moment.

Together, these concepts create a continuum of knowledge that supports both the intellectual and artistic development of dancers and educators. Ballet Continuum Model

🧩 Common Elements between Dance History & Dance Theory

1. Cultural and Social Context

Both dance history and dance theory emphasize cultural and social influences. Dance, in any historical period, is closely tied to its cultural context—whether rooted in religious traditions, folk customs, or modern artistic movements. Dance theory explains how these influences shape dance styles and forms. Dance history documents the changes and developments that occurred due to these social and cultural factors.

2. Evolution of Styles and Techniques

For example, the history of ballet outlines its journey from the royal courts of France to modern theaters, while ballet theory examines posture, technique, and the vocabulary of the style. Dance history tracks the stylistic changes from ritual dances to classical ballet, modern, and contemporary dance. Dance theory analyzes these styles and techniques, offering the tools to understand and classify them.

3. Ritual and Symbolism

From both historical and theoretical perspectives, ritualistic and symbolic dance has played a central role in indigenous and religious cultures—and remains a major topic in modern dance studies. Dance history records these expressions and their social function in ancient societies. Dance theory explores the symbolism and meaning of these movements, explaining how dance can express abstract ideas or religious themes.

4. Functions of Dance in Society

History and theory both recognize the multiple roles dance plays in various contexts. Dance can serve as entertainment, ritual practice, a form of national identity, or a tool for social protest. Dance theory investigates how and why these functions exist. Dance history documents the times and places where dance had a significant societal impact.

5. Relationship Between Dance and Other Arts

In classical ballet history, for example, music and choreography have always gone hand in hand. Dance history shows how dance has often developed in relation to other art forms—such as theater, music, poetry, or visual arts. Dance theory examines how these disciplines interact and influence movement and style.

6. Movement as Language

Both history and theory consider movement as a universal language. Dance history documents the periods and styles where dance was used as communication or aesthetic expression. Dance theory analyzes this "language" from semiotic and philosophical perspectives, studying how movements are interpreted across cultures and time.

7. The Body and Technique

In both areas, the body and technique are essential components.

For example:

Modern dance theory explores the role of gravity, breath, and center of weight in movement. Modern dance history shows how these techniques were introduced by choreographers like Martha Graham or Isadora Duncan.

Dance history reveals how techniques evolved based on dominant styles and the function of dance (religious, social, artistic). Dance theory dives deeper into studying the body as a central instrument of dance practice.

8. Aesthetics and Artistic Value

For example:

Postmodern dance history shows how the art moved away from codified forms. Postmodern theory explains the rejection of traditional conventions in favor of authenticity and movement diversity.

Dance history traces the evolution of dominant aesthetics—from the symmetry and order of classical ballet to the fragmentation of contemporary dance. Dance theory provides the tools to analyze and evaluate these aesthetics, discussing beauty, expression, innovation, and artistic value.

9. Philosophical and Theoretical Influences

Throughout history, dance has been influenced by different philosophical and theoretical movements.

Modern and contemporary dance, for example, often drew from existentialism, phenomenology, or psychoanalytic theory. Dance theory explores these influences in depth, analyzing how choreographic approaches reflect philosophical ideas. Dance history documents when, where, and by whom these ideas were introduced.

🧩 Common Elements between Dance Theory & Dance Aesthetics

1. Beauty and Bodily Expression

Both disciplines study how bodily movements can communicate emotions and ideas, whether abstract or concrete, and how these influence the aesthetic perception of dance. Dance theory explores how movements can be learned and applied to achieve expression and beauty. Dance aesthetics seeks to define concepts such as beauty and harmony in movement, analyzing what makes a dance appear "beautiful" or "impressive."

2. Harmony and Balance

The concept of balance and harmony is central to dance, and both fields address it in depth. Bodily harmony and movement equilibrium are core to understanding both perspectives. Dance theory analyzes the techniques and principles that lead to balanced movement. Dance aesthetics focuses on how movements are harmonized to create a visually and emotionally pleasing experience.

3. Relationship with Music and Rhythm

Both disciplines emphasize the importance of rhythm and synchronization in dance, both from a technical and aesthetic point of view. Dance theory investigates how dancers adapt movement to match rhythm, tempo, and musical dynamics—shaping the aesthetic result. Dance aesthetics examine how movement aligns with music to produce a unified and coherent artistic experience.

4. Form and Style

Form and style are examined in both fields to understand what contributes to a unique and effective aesthetic experience. Dance theory analyzes and classifies various dance forms and styles (classical, modern, contemporary, etc.) based on structure and technique. Dance aesthetics look at those same forms and styles from the perspective of visual and emotional impact, exploring what makes a style artistically appreciated.

5. Improvisation and Spontaneity

Both approaches acknowledge the value of improvisation in dance as a tool for creative expression and its contribution to the uniqueness of a performance. Dance theory studies improvisation in terms of technique and the skills required to execute it effectively. Dance aesthetics value improvisation for its ability to generate authentic, spontaneous, and expressive movement that may be perceived as beautiful or innovative.

6. Emotion and Symbolism

Both dance aesthetics and theory are concerned with how dance conveys emotion and symbolic meaning. Emotion is essential to the aesthetic perception of dance, while theory explores how dancers amplify expressive content. Dance theory focuses on the structure and mechanisms that allow the body to express these ideas. Dance aesthetics examines how those emotions and symbols are perceived and artistically valued by an audience.

7. Originality and Innovation

Both disciplines appreciate dance's capacity to evolve and introduce new elements that not only respect but also surpass existing conventions. In dance theory, originality is discussed in terms of choreographic innovation and new techniques that can redefine the limits of dance. In dance aesthetics, originality is a key criterion for evaluating a performance or style, viewed as a valuable trait that contributes to artistic appreciation.

8. Interaction Between Dancer and Audience

The connection between performer and audience is essential in creating a successful aesthetic experience. Both disciplines explore how this connection can be cultivated. Dance theory addresses the dynamics of performance and how the dancer uses space and movement to engage and influence the audience. Dance aesthetics focuses on how performances are perceived by the audience and how this relationship shapes the artistic experience.

9. Movement Aesthetics and Technique

Technique and aesthetics are closely linked, as well-executed technique enhances the aesthetic impact of a performance. Dance theory explains the technical foundations of movement and how they lead to aesthetic results, defining how movement should be performed to be considered "beautiful" or expressive. Dance aesthetics focuses on the visual qualities of movement—fluidity, grace, strength—and its emotional impact on the viewer.

10. Cultural Context and Traditions

Both fields recognize the influence of cultural traditions on how dance is practiced and appreciated. Dance theory analyzes dances from various cultures and traditions, examining how techniques and styles vary across historical and cultural contexts. Dance aesthetics value the diversity and beauty of these traditions, analyzing how culture shapes the aesthetic perception of dance.

🧩 Common Elements between Dance Aesthetics & Dance Style

1. Form and Visual Structure

Dance aesthetics focuses on the visual aspects of movement—such as beauty, balance, and harmony in the body’s motion—and how these movements are perceived as pleasing or meaningful. Dance style refers to the specific way movements are organized. Each dance style (ballet, modern, contemporary, hip-hop, etc.) has a distinct visual structure that contributes to the overall aesthetic of a performance.

2. Expressiveness and Emotion

Aesthetics explores how dance communicates emotions and ideas through movement, evaluating how expressive and emotionally resonant a performance is—crucial for appreciating its beauty and meaning. Style largely determines how emotions are expressed. For example, classical ballet tends to be more formal and graceful, while contemporary dance allows for freer and more emotional expression. The aesthetics of each style are tied to its specific expressive character.

3. Originality and Innovation

Dance aesthetics value originality in the way movements are presented and perceived. An innovative aesthetic can redefine what is considered beautiful or interesting in dance. Style is often the place where originality appears. While traditional styles have established rules and conventions, dancers and choreographers can innovate within or beyond these frameworks to create a unique aesthetic.

4. Rhythm and Dynamism

Dance aesthetics evaluate rhythm and movement fluidity, focusing on how dynamics and synchronization affect the viewer’s perception. Style defines the rhythm and dynamic quality of movement within each genre. For example, urban dance styles like hip-hop feature very different rhythms and energy compared to classical ballet, shaping the aesthetic experience of each.

5. Costumes and Visual Presentation

Dance aesthetics also include visual presentation—such as costumes, set design, and lighting—which all contribute to the audience’s aesthetic experience. Style influences costumes and visual presentation, as each style has specific aesthetic expectations for attire and staging. For instance, classical ballet uses elegant costumes and tutus, while contemporary dance may opt for minimalist clothing.

6. Cultural Influence

Dance aesthetics are often shaped by the cultural and historical context in which it is created. Perceptions of beauty and movement vary across cultures. Style is also determined by the culture it originates from. For example, traditional African or folk dances have distinct styles that reflect the cultural and historical values of their communities, and the aesthetics of these styles are appreciated differently than Western dance forms.

7. Symbolism and Meaning

Dance aesthetics examines the symbolism in movement and how it conveys messages or emotions to the audience. Style deeply influences the meaning of movement. Each style has its symbolic vocabulary—for instance, precise gestures in ballet may carry strong symbolic weight, while abstract movements in contemporary dance may invite open interpretation.

8. Audience Impact

Dance aesthetics considers how a performance is perceived by the audience and the emotional or visual impact it creates. Style influences how the audience experiences a performance, as each style creates different expectations and involves specific modes of

The Power of Presence: Ballet, Beauty, and Becoming at NdB

An essay inspired by the 4th reprise of Don Quixote, performed by the Ballet of the National Theatre Brno on May 2, 2025.

Pictures@NdB - New Principals at NdB

In the luminous space of the Janáček Theatre, the 141st season of the National Theatre Brno unfolded with elegance and passion, presenting the fourth reprise of Ludwig Minkus' Don Quixote under the poetic choreography of José Carlos Martinez. More than a performance, it was an act of cultural celebration and embodied artistry—one that culminated in the well-deserved promotion of the interpreters of Kitri and Basil to the rank of principal dancers within the company.

Honoring the dancers of the NdB is to acknowledge a discipline that transcends physical effort. It is to witness the convergence of cognitive intention and emotional precision. The role of Kitri, danced with spirited finesse by Momona Sakakibara, was a marvel of character-driven interpretation. She did not merely dance; she became Kitri. Likewise, Shoma Ogasawara brought Basil to life with masculine energy and lyrical athleticism, forming a dynamic and compelling partnership with Sakakibara’s Kitri. Their chemistry animated the stage with vitality and charm. Captivating was also the pairing of Se Hyun An as the fierce and seductive Mercedes with Adam Ashcroft’s elegant and commanding Espada—a duet that radiated passion, tension, and stylistic contrast.

This performance was also a testimony to ensemble excellence. From Nanaka Ogawa's ethereal Dryad Queen to the precise ensemble work of the corps de ballet, each role served a purpose in the narrative tapestry. Supporting roles like Sancho Panza (Hugo Martinez) and Don Quixote (Dillon Perry) reminded the audience that humor and poetry can coexist seamlessly on stage.

Behind this brilliance stood a dedicated creative team: costume designers Iñaki Cobos Guerrero and Roman Šolc, scenographers, choreographic assistants, lighting designers, and musical directors who breathed structure and atmosphere into the vision. Their work exemplifies that ballet is never the sum of isolated efforts but a synthesis of vision, memory, discipline, and art. Perhaps the most important figure in setting the artistic tone of the company, however, remains the artistic director.

At the helm of the National Theatre Brno Ballet is Mário Radačovský, whose leadership since the 2013/2014 season has been instrumental in elevating the company's artistic profile. A Slovak native, Radačovský's illustrious career began after graduating from the Eva Jaczová Dance Conservatory in Bratislava. He joined the Slovak National Theatre Ballet in 1989, quickly rising to the rank of soloist. His international experience includes performing with Jiří Kylián’s Netherlands Dance Theatre, where he collaborated with renowned choreographers such as Mats Ek, Nacho Duato, Ohad Naharin, William Forsythe, and Édouard Lock. In 1999, he became the principal dancer of Les Grands Ballets Canadiens in Montreal. Returning to Slovakia, he served as the Artistic Director of the Slovak National Theatre Ballet from 2006 to 2010 and later founded Ballet Bratislava. In 2018, he completed a master's degree in choreography at the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague.

Radačovský's vision for the Brno company emphasizes a balance between classical and contemporary repertoire, aiming to transform it into a world-class ensemble. In addition to his artistic programming, he has enhanced the company's structure and long-term sustainability by introducing NdB2, a youth company that nurtures emerging talent, and NdB3, a platform for elder dancers—both inspired by the model of Jiří Kylián. These initiatives have added significant value to the institution, expanding its social and generational relevance.

To honor the ballet dancers of NdB is to honor the deep intelligence of the body, the endurance of tradition, and the power of ephemeral beauty made visible, night after night—a true manifestation of the power of presence that gives meaning to ballet, beauty, and becoming.

Functions and Relevance of Higher Studies in Classical Dance

Sir Peter Wright rehearsing Simona Noja in the role of Aurora (Sleeping Beauty)

The question "What is the purpose of higher studies in classical dance?" touches the core of the value of education in performing arts. In the case of academic ballet, the answer involves a complex, interdisciplinary, and profoundly formative approach:

a) Formation of Conscious Artists, Not Just Performers: A cultivated dancer, familiar with the history, aesthetics, and stylistics of ballet, becomes:

An interpreter with depth and artistic intention;

A bodily communicator capable of conveying meaning, context, and emotion;

A responsible creator, aware of the tradition they belong to and the impact of their own approach.

b) Development of a Critical Basis for Research and Innovation: University studies in classical dance offer openness to fields such as:

Dance anthropology – for understanding the phenomenon in a socio-cultural context;

Aesthetics – for investigating how dance produces emotion, symbol, and meaning;

Stylistics – for differentiating between various schools and pedagogical approaches;

Dance theory and methodology – for grounding pedagogy and choreographic creation.

Through this, the dancer becomes a researcher, pedagogue, and innovator simultaneously.

c) Dialogue Between Classical Dance and Other Arts or Social Domains: Through knowledge of history and theory, the student understands:

The evolution of dance depending on social, political, and cultural context;

Connections between dance and other arts – music, painting, literature, theater;

The role of dance in contemporary artistic responses to themes such as identity, gender, or globalization.

An educated dancer becomes an agent of artistic reflection and a bodily thinker, not just a spectacular performer.

d) Diversification of Career Opportunities: A graduate of a classical dance program can access multiple professional roles:

Ballet teacher or coach;

Choreographer with an articulated aesthetic vision;

Dance critic, researcher, or movement dramaturge;

Cultural manager, curator, or artistic consultant.

Without a solid theoretical foundation, many of these options remain inaccessible.

e) Dignity and Legitimacy of the Art of Dance: Dance is often marginalized as a "decorative" or "inferior" art. Academic study:

Elevates it to the level of an intellectual and analytical art;

Provides it with a legitimate framework in academic culture;

Allows the integration of dance into national and international

Conclusion:

A higher education in classical dance represents more than just professional training—it is a form of intellectual deepening, a humanization of artistic practice, and an opening toward interdisciplinary dialogue. It prepares artists who not only perform dance but also understand it, analyze it, teach it, and develop it, transforming it into an act of reflection and knowledge.

#dancehigheducation #simonanojanebyla #dancetheory

Amintindu-mi-l pe Béla Karoly sau despre gimnastica de performanță și înțelegerea depășirii de sine

În toamna târzie a lui 1977, la un concurs național de gimnastică, antrenorul Echipei olimpice de gimnastică sportivă a României, nimeni altul decât Béla Károlyi, antrenorul Nadiei Comăneci, în căutare de talente, m-a remarcat în concursul de la sol, unde, uitând coregrafia, am improvizat toată evoluția. Cu atât mai mare a fost surpriza mea, când am aflat că în urma concursului au fost selecționate doar două gimnaste să intre în Echipa olimpică de la Onești. Una dintre ele eram eu. Aveam 9 ani.

Cantonamentul de două săptămâni la Oradea în ianuarie 1978 cu echipa olimpică, din care între timp Nadia Comăneci plecase, urmat de călătoria la București, de stagiul de la Onești și perioada de tranziție a întregii echipe la Deva în Transilvania, la noul centru specializat de antrenament sportiv, sunt primele mele întâlniri cu marea performanță.

Aveam două antrenamente pe zi: între orele 8-11 și după amiaza între orele 17-20. Între timp luam masa de amiază și aveam scoală. Cred că eram în totalitate nu mai mult de 10 gimnaste, care ne antrenam cu Béla Károly, cu soția lui, Márta Károlyi și profesorul de dans, Geza Pozsar. Aveam un medic specializat și o guvernantă. Prietena mea era Lelia Cristina Itu, gimnastă și ea, mai mare decât mine, tot din Cluj.

Pentru cei dinafară sportului de performanță, a te antrena 6 ore pe zi, a te cântari săptămânal și a-ți dedica în întregime timpul în ceea ce crezi înseamnă sacrificiu. Pentru mine, copilul de atunci a fost pasiune și bucurie, stare sufletească pe care din fericire am trăit-o apoi și ca adult.

Desigur că nu au fost doar momente fericite. Într-o după-amiază trebuia să execut un salt complicat pe bârnă, aparatul preferat al Mártei Károlyi și i-am mărturisit că îmi era frică. Mi-a spus să fac genoflexiuni în locul exercițiului. Am făcut. Am ajuns la 1000 de repetiții când mi-a dat voie să mă opresc. În mod ciudat, nu am avut nicio febră musculară. Doar la discuția telefonică cu părinții mei, aflând vestea pe care le-am dat-o cu seninătate, amândoi au intrat în panică. Ei mă vedeau încă foarte fragilă… Bănuiam eu că ceva era poate ușor exagerat… dar nu știam cu exactitate dacă era de bine sau de rău…

Am ales să cred că era de bine. Mă gândeam că experiența îmi va servi cândva. Așteptam cu nerăbdare viitorul...

Aventura mea în Lotul olimpic avea să se încheie înainte de olimpiadă. Dincolo de grija părinților mei față de fragilitatea mea, mai era o cauză, ce ținea de concepția lor față de prioritatea pe care cultura generală trebuie să o ocupe în educația copilului lor. Și aici lucrurile nu erau chiar în ordine din punctul lor de vedere. În Lotul olimpic eram fete între clasa a IV și clasa a XII-a, iar cursurile se țineau în același spatiu, în același timp, cu aceeași profesori. Era cert că în Lotul Olimpic performanta gimnasticii sportive devansa performanța intelectuală. Perspectiva de a avea o fiică mai mult sau mai puțin analfabetă, nu intra deloc în planurile familiei Noja.

Era de bine? Era de rău?

Aveam 10 ani. După o carantină provocată de îmbolnăvirea cu rujeola, în care am fost îngrijită de bunica mea maternă, Buna, venită de la Mănăstireni la internatul din Deva special pentru a mă îngriji, zarurile destinului meu au fost aruncate. La începutul verii anului 1978 am fost retrasă cu acordul meu tacit din Lotul olimpic de gimnastică. Și totuși, în adâncul sufletului, credeam că orice șansă de a deveni celebră (doar doream să devin o noua Nadia Comăneci!) mi-a fost spulberată. Dacă nu voi deveni celebră în gimnastica sportivă, în ce direcție mă vă purta oare destinul?

Probabil că atunci s-a născut ideea mea de a deveni bibliotecară. În percepția mea de copil la 10 ani, căruia îi placea să citească, consideram bibliotecarii ca pe niște privilegiați ai sorții. Se află atât de aproape de înțelepciune…O pot atinge cu mâna. Oricând. A medita în liniștea unei biblioteci, a trăi în vecinătatea cărților, departe de tumultul lumii, a citi la liberă alegere texte plină de inspirație și a avea libertatea de a ignora textele “neprietenoase” au fost atunci, și au rămas până în ziua de azi, dorințe profunde.

Contactul meu cu echipa olimpică a fost primul meu pas spre extrema performanță. Trăind prin experiența imediată minunile de care corpul uman este în stare, într-un mediu benefic de stimulație și înțelegere profundă a fenomenului, antrenându-mă cu o echipă competentă de antrenori și medici, alături de alte gimnaste cu aceleași vise și aspirații ca și mine, am înțeles că totul este posibil.

Atunci și acolo am învățat că prin munca asiduă orice piedică poate fi depășită.

Faptul că toți cei trei antenori (Béla, Marta și Gesza) erau în fiecare zi în sală timp de 6 ore, fără cea mai mică urmă de oboseală sau plictiseală, faptul că în timpul său liber medicul echipei alegea să opereze pacienți în spital pentru a nu-i lasă să moară, au devenit etaloane de înaltă moralitate educațională. Acele memorii îndepărtate s-au făcut vizible instantaneu și cu mare exactitate în momentul când am început să devin eu însămi pedagog și mentor și au devenit făclii incandescente, deschizătoare de drumuri, în momentul teoretizării propriei mele experiențe. Chiar dacă profesia de balerin este diferită de cea de gimnast, modele umane de pedagogi avuți în copilărie și pe tot parcursul educațional, m-au influențat profund. Acum, decenii mai târziu, le sunt mai mult decât recunoscătoare tuturor antrenorilor din sport, care conștient sau nu, prin propriul model mi-au format caracterul și gustul mișcării performante.

În cazul meu, prin sport l-am înțeles pe Protagoras și dictonul său conform căruia “Omul este măsura lucrurilor”.

Oricum, gimnastica mi-a dat o rezistență fizica cu urmări benefice pentru condiția de balerină și mi-a sugerat convingerea că performanța începe odată cu concurența ta cu tine însăți, că de fapt, piedicile pe care viață ți le scoate în cale nu sunt decât măsurători oficiale ale unei permanente competiții cu tine însăți.

Și timpul mi-a dat dreptate. Nouă ani mai târziu, în 1987, la debutul meu în rolul principal “Kitri” din baletul “Don Quijote” tempo-ul fouétte-urilor din actul al treilea a fost atât de rar, încât în loc de 32 a trebuit să fac 64 de fouétte-uri. Având experiența celor 1000 de genoflexiuni făcute fără pauză, a te învârti cu viteza și cu o coordonare precisă pe un picior doar de 64 de ori, a fost doar o încercare neprietenoasă. Avusesem o inspirație de bun augur în urmă cu 9 ani să nu mă victimizez.

Performanța începe în momentul în care îți asumi destinul și decizi … fără a ști cu exactitate ce se va întâmpla după.

Acest crez mi s-a confirmat în cadrul aceluiași spectacol, când dirijorul a luat niște decizii stângace. Era o stare de maximă concentrare, o tensiune ridicată, ca de premieră, când în actul al treilea după ce variația mea a dirijat-o mai mult decât dezlânat, partea cea mai spectaculoasă din spectacol, coda cu fouétte-urile a ratat-o grandios cum am amintit mai sus...și cea de-a doua codă a mea, care ar fi trebuit să fie culminația apoteotică a unui pas de deux de mare temperament, în loc de allegro o începuse ca un adagio… Aveam 19 ani, era debutul meu într-un rol de bravură la care lucrasem cu dăruire de-a lungul mai multor luni, sala Operei Naționale Române din Cluj-Napoca plină ochi și eu ...pornisem deja furibund într-un manej de pique-uri...

Sunt momente în existența noastră, unde totul se joacă pe o carte. Diferența între a fi și a nu fi este la distanță de o membrană cum spunea Bainbridge Cohen, inițiatoarea disciplinei somatice numită Body-Mind-Centering… Spațiul devine câmp deschis, imponderabil, timpul se eliberează de ritm, devenind atemporal…. Este momentul în care o secundă poate fi o eternitate (Lewis Caroll)...Este momentul când rațiunea și-a epuizat resursele. Momentul prezent devine doar emoție… un câmp atemporal și aspațial…

În acel moment, îmi place să cred, că mișcarea mea a devenit cuvânt. Cuvânt eliberat de materie, cuvânt care prefera să-și poarte/ înțelesul pe dinafară (Ion Noja). Și l-am strigat din adâncul sufletului în plin manej:TEMPO! A fost cu totul neașteptat. Dirijorul l-a auzit, orchestra l-a auzit, o sală întreagă l-a auzit.,, și a început să aplaude frenetic; și eu, finalizând entuziast spectacolul... eliberată de prejudicii în căutarea adevărului, începeam să înțeleg menirea mea artistică... Nu doar gândul, ci și mișcarea putea deveni cuvânt. Era un început? Era un sfârșit? Era de bine? Era de rău?